One of the biggest issues when it comes to game development is designing a comprehensive, responsive and elegant GUI (Graphical User Interface) system. To the surprise of most non-developers, creating buttons and windows for your game can be more frustrating than creating models with thousands of polygons, or animating rigs; especially if your chosen game engine is a 3D engine like Unity.

It all boils down to functionality. The game’s GUI is the only thing that stands in the way between the player and the game. A game starts and ends with the press of a button on your screen. The player might quickly forget a glitchy model that doesn’t display its texture properly, but a single unmovable window in the way of his firing aim, or a button that doesn’t always respond to his mouse input might cause him to discard the game and never touch it again.

Designing a proper GUI however, requires a proper framework supporting it. And here’s where video games make it hard. If a game is developed right, no two single games should look the same.

Each game has its own layout, its own GUI needs, and its own style of depicting that GUI on your screen. This fact alone makes designing a framework that supports more than a single unique game a nightmare, since it can get bloated quickly with options and functions that will never be used for more than one game.

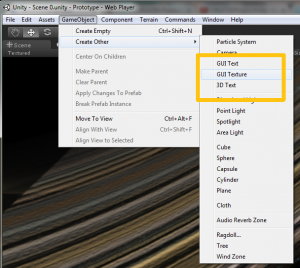

And this is where Unity both fails and shines at the same time. Unity has made two attempts so far at a proper GUI Framework. Their first attempt came in the form of TextMeshes, GUITextures and GUITexts, three very simple primitive 3D objects that did nothing on their own without heavy coding supporting them, from the part of the developer.

The second GUI system, called OnGUI to differentiate it from the old GUI framework, chose a completely different approach. The entire GUI layout would now be written in pure code, without visual representation during the level design process. However, it would come with all sorts of options, like scrollable window menus, function ready buttons, and CSS-like styling. The issue this time was performance. A badly designed GUI framework can drop a game’s frame rate a lot more than multiple stacked post processing effects. And Unity’s OnGUI was an example of bad design.

OnGUI completely discarded .NET’s object oriented, fire and forget coding, in favor of a convoluted and bloated state machine that ran multiple times per frame and drained CPU cycle resources, cluttered with statements, checks and boolean switches. The end result for something a bit more complicated than a single menu button was a mile long spaghetti code that was unmanageable to say the least.

In addition, OnGUI tried to offer to the developer instant modability, allowing him with frame level precision to remove, change, reorient or add new GUI elements. This, however meant that no two GUI elements could share the same atlas anymore to make use of rendering optimizations, and the entire system would need to draw each GUI element at the beginning of the frame, and destroy it after it had been rendered, over and over, frame after frame, generating huge ammounts of garbage every frame on RAM.

Unity is currently designing its 3rd attempt on a GUI System, but also allows developers to create our own frameworks, that, surprisingly, turn out even better than Unity’s native GUI frameworks. On Unity’s asset store we have downloadable packages like EZGUI, and nGUI, that do everything Unity’s GUI do and more, at 1/10th of the resource costs.

Here, at CREAT3D, after some thought, we decided to develop our own GUI framework that will address game-level requirements that generic frameworks couldn’t possibly do. We call this GUI MagicGUI, and it will be used by all our future projects.

![unityLogo[1]](https://creat3d.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/unityLogo1.png)